By Arie Kizel

In a world where adult voices often

dominate the discourse, it's crucial to create spaces where children can

express their ideas, ask questions, and develop their critical thinking.

Philosophical communities of inquiry offer a powerful framework for enabling

children's voices, fostering an environment where their curiosity is valued and

their thoughts are taken seriously.

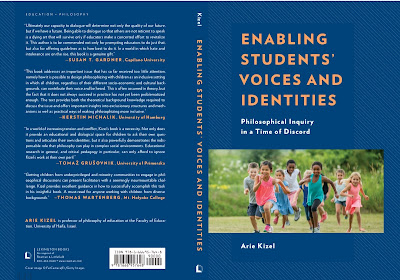

In my book, "Enabling Students'

Voices and Identities: Philosophical Inquiry in a Time of Discord," I

discuss the importance of this approach not only for enabling voices but also

for enabling students' identities.

What Are Philosophical Communities

of Inquiry?

Philosophical communities of inquiry

are a pedagogical approach that encourages children (and adults) to engage in

rigorous philosophical discussion. At the core of this approach is the

assumption that children have a natural capacity for philosophical thought and

are capable of grappling with fundamental questions about morality, knowledge,

existence, and justice. Unlike traditional philosophy lessons, where an expert

transmits knowledge, philosophical communities of inquiry focus on a

collaborative process of inquiry. Within a community of inquiry, participants

sit in a circle, often around a thought-provoking question or text, and engage

in a conversation that exemplifies dialogue at its best. The facilitator (or

mentor) does not provide answers but can (though not always) encourage active

listening, argument construction, presentation of evidence, and the acceptance

of different perspectives. The goal is not to arrive at a single "correct"

answer, but to deepen understanding and develop critical and creative thinking

skills.

How Do Philosophical Communities of

Inquiry Enable Children's Voices and Identities?

Children are not just "blank

slates" waiting to be filled with knowledge; they possess

"philosophical freshness" and an inventive ability to ask fundamental

questions. In my book, I challenge rigid psychological-developmental perceptions

that often limit the recognition of children's innate philosophical skills. In

my view, "philosophy with children" is not a lesson where children

are taught to philosophize, but rather the creation of a space where the human

mind operates naturally, through conversation, listening, and asking questions.

Valuing Curiosity and Independent

Thinking:

Communities of inquiry recognize

that children are not just passive recipients of information but active

thinkers. They legitimize their complex, sometimes "naive," questions

and show them that curiosity is a driving force for thought. When a child asks,

"Why do we exist?" or "What is justice?", the question is

taken seriously as a starting point for discussion, not as an interruption or

an unanswerable question. Sometimes they point out that children, even those

whose voices are silenced in the school environment, sometimes find

philosophical expression in virtual spaces, where they ask existential

questions like "Did the world have a beginning?" or "Is all this

a dream?".

Fostering Self-Confidence in

Expression and Enabling Identity:

In an environment where listening

and participation are equally valued, children feel more secure in expressing

their opinions, even if they differ from others. They learn to articulate their

thoughts clearly, defend their positions, and change their minds in light of

new evidence. This experience builds self-confidence and encourages them to be

more active in discourse, even outside the community framework. In my book, I

expand the concept of "voice" to "presence and identity,"

emphasizing the challenge of enabling silenced voices, especially those of

oppressed groups, within philosophical communities of inquiry. In doing so, the

community becomes a space where children can build and express their unique

identity.

Developing Listening Skills and

Mutual Respect:

One of the core principles of

communities of inquiry is empathetic listening. Children learn to listen to

what others say, to understand their perspective, even if they disagree with

it. This process fosters mutual respect, tolerance, and a willingness to engage

in constructive dialogue, rather than confrontation. When they hear themselves,

they learn the value of enabling others to be heard. In my book, I note that

children, who are sometimes perceived as egocentric, are willing to recognize

the extraordinary ideas of their peers as a resource for them, leading to

attentive listening and connection.

Recognizing Emotional and Social

Intelligence:

Philosophical discussions are not

merely dry intellectual matters. They often touch upon deep emotional and

social issues. Children develop the ability to identify emotions in themselves

and others, to understand the impact of emotions on thinking, and to make

informed moral decisions. They learn that emotions also have a legitimate place

in discourse.

Improving Critical and Creative

Thinking and the Search for Meaning:

Communities of inquiry challenge

children to think beyond the obvious. They learn to analyze ideas, identify

hidden assumptions, evaluate arguments, and consider alternatives. This process

enhances their critical thinking skills, enabling them to be more critical

consumers of information in a complex world. At the same time, they are

encouraged to think creatively and seek innovative solutions to problems. In my

book, I link philosophical communities of inquiry to the search for meaning and

the development of a sense of responsibility, inspired by thinkers like Matthew

Lipman and Emmanuel Levinas. I see this as a basis for developing recognition

of the existential uniqueness of everyone.

In my opinion, one of the central

challenges he identifies is the dominance of what he calls the "pedagogy

of fear."

What Is the Pedagogy of Fear?

The pedagogy of fear is an

educational approach, explicit or implicit, based on creating a sense of

anxiety or apprehension among both students and teachers. Instead of

encouraging curiosity, inquiry, and free thought, it focuses on obedience,

standardized performance, and the reduction of uncertainty. I would now like to

point out several manifestations of this pedagogy in the education system:

- Fear

of failure: Among

both students and teachers, there is a constant fear of failure in tests,

assessments, or not meeting expectations. This fear often leads to

avoiding intellectual risk and thinking outside the box.

- Fear

of making mistakes: The

education system sometimes labels mistakes as failures rather than

opportunities for learning. The emphasis on the "correct answer"

deters students from raising unconventional ideas or asking

"silly" questions.

- Fear

of the unusual and unpredictable:

The pedagogy of fear prefers order, discipline, and predictable outcomes.

Philosophical inquiry, by its very nature, is an unpredictable process

that raises new questions and challenges fundamental assumptions and

therefore may be perceived as a threat to control and classroom order.

- Fear

of undermining authority:

Philosophical communities of inquiry blur the traditional boundaries of

the teacher's authority as the sole expert. They encourage open discussion

where ideas are judged by their logical strength, not by the status of

whoever expressed them. This can cause apprehension among teachers who are

not accustomed to relinquishing absolute control over the discourse.

- Fear

of inefficiency: In an era

where the emphasis is on metrics, "acceptable" achievements, and

crowded curricula, philosophical communities of inquiry can be perceived

as a "waste of time" or an activity that is not

"efficient" enough to achieve narrow educational goals.

The Impact of the Pedagogy of Fear

on Philosophical Communities of Inquiry

The pedagogy of fear creates a

climate that is not conducive to the flourishing of philosophical communities

of inquiry:

- Silencing

voices: Instead

of encouraging children to express their thoughts, the fear of criticism

or failure causes them to prefer silence or to repeat predictable answers.

Their voice, both philosophical and personal, remains silenced.

- Suppressing

curiosity: Instead

of fostering children's natural curiosity, the emphasis on memorization

and exams suppresses the desire to ask deep, inquisitive questions.

- Harming

authenticity: Children

are afraid to be who they truly are, to express themselves freely, and to

raise questions stemming from their inner world, which harms their ability

to build an authentic identity within the community.

- Difficulty

in genuine listening: When

everyone is afraid, it is difficult to develop the mutual respect and deep

listening required for meaningful philosophical dialogue.

Moving from a Pedagogy of Fear to a

Pedagogy of Enabling

In my book, I point out that

philosophical communities of inquiry offer a central way to overcome the

pedagogy of fear. They create a safe space where:

- Mistakes

are part of the process:

Mistakes are not seen as failures but as opportunities to deepen

understanding and refine thinking.

- Curiosity

is legitimized:

Questions, even the strangest ones, are welcomed as a starting point for

deep discussion.

- Diversity

is valued: Different

perspectives enrich each other, fostering respect and tolerance.

- The

teacher is a facilitator, not just an authority: The teacher's role changes from an

exclusive source of knowledge to a facilitator who helps children discover

on their own.

For philosophical communities of

inquiry to thrive, a profound cultural change is needed in the education system

– a change that requires courage from both teachers and decision-makers to

relinquish absolute control and adopt an approach based on trust, curiosity,

and true enabling of students' voices and identities.

Challenges and Solutions

Although philosophical communities

of inquiry offer many benefits, there are also challenges in their

implementation. These include training skilled facilitators, finding time in a

busy schedule, and adapting content to different ages and developmental abilities.

However, the benefits of nurturing a generation of independent, confident, and

dialogically capable thinkers far outweigh the challenges. Investing in teacher

training and developing flexible curricula can help overcome these obstacles.

Concluding Remarks

Philosophical communities of inquiry

are not a method for teaching philosophy to children; they are a way to build

dynamic thinking communities where every child's voice is heard, valued, and

enabled. By providing a platform for children to explore life's big questions,

we not only develop their intellectual capabilities but also empower them to

build their identity, become engaged citizens, critical thinkers, and

empathetic human beings. Enabling children's voices and identities through such

approaches is an investment in a better future, where the voices of the next

generation will receive the respect they deserve.

אין תגובות:

הוסף רשומת תגובה